THE MINORITY REPORT

DEV KUMAR SUNUWAR

Four-year-old Siriya Shahi from Inatol in Kathmandu is a shy girl if you try to talk to her in Nepali. As she doesn’t speak or understand Nepali, she prefers to stay quietly in a corner of the classroom and doesn’t participate in school activities. But talk to her in her native language, Newar, and she springs to action.

Shahi is one of 13 students enrolled at the nursery level at Jagat Sundar Bwonekthi Secondary School at Lakhu Tirtha of Chagal in Kathmandu.

Situated in the south of the Bisnumati River and by the Dallu bridge, it is the first school established in the Kathmandu Valley to teach children in their mother tongue – Newari, or Nepal Bhasha.

Drawing from the experience from different parts of the world, Maya Manandhar, the school principal, says that children who start their preschools in their mother tongue develop strong basic academic skills, systematically acquire the national and then international languages, and perform much better in school exams.

The school’s track record validates her observation: Out of the school’s first batch of 14 students who appeared in the School Leaving Certificate Examinations six years ago, nine passed with distinction while the rest secured first division. Of the 18 students who appeared in the last SLC exams, two have obtained distinction while the rest passed in the first division.

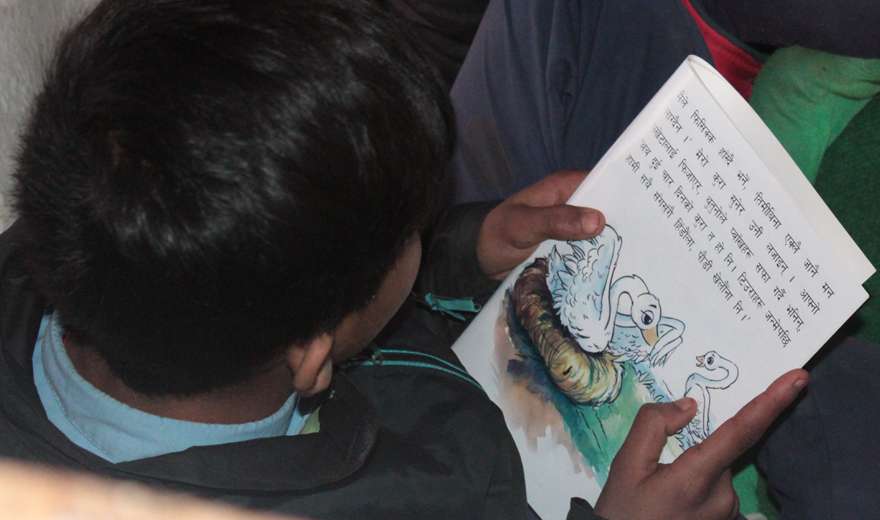

Besides the curriculum developed by Curriculum Development Center (CDC) in the Newar language, the school has also prepared its own textbooks and other reading materials, and has also composed school anthem and songs after discussions with Newar language experts.

The Modern Newa English School at Durbar Marg, established in 2003, is another school in Kathmandu that is promoting elementary education in Newari.

Its founder, Deepak Tuladhar, and his team have launched a drive to set up at least one school in each Newar settlement with Newari as a medium of instruction.

According to Tuladhar, nearly one hundred schools across Nepal have already started including Newari language in their curriculum, either as the medium of instruction or a subject of study.

They include private schools such as Rato Bangla School, Siddhartha Banasthali and Malpi International School in Kathmandu.

But not all the children from all the Indigenous Populations (IPs) are that fortunate.

An overwhelming majority of the children, primarily from different IPs and linguistic minority groups whose first language is neither Nepali nor English are taught in Nepali and English languages in the classroom. This has led to an increased number of dropouts and poor achievements for the students from non-Nepali-speaking communities.

Nepal is a multilingual country with more than 123 living languages, according CBS Census 2011. As Nepali, the official language, is not the mother tongue of 56.4% of the total population, linguists opine that learning in a language which is not their mother tongue poses challenges to such children.

Allowing children to learn in the language they speak at home instills pride and helps build confidence. Depriving children of their mother tongue during early years can adversely impact their linguistic and overall performances.

“Allowing children to learn in the language they speak at home instills pride and helps build confidence,” says Amrit Yonjon Tamang, a linguist. “Depriving children of their mother tongue during early years can adversely impact their linguistic and overall performances.”

According to him, a child has a high capacity to learn multiple languages during the early years. But it is their mother tongue in which they can express to the fullest and learn to the maximum. More importantly, it is their right to get education in their mother tongue as a medium of study and not as a subject, at least up to the secondary level, as provisioned by the Interim Constitution of Nepal. But children from linguistic minorities and IPs have been deprived of this very basic and inalienable right.

Unequal access to education

Clear statistical data on the status of education or other indicators on the quality of life, specifically of IPs and other minority groups in Nepal are very hard to find. However, a few studies show that children from these groups still don’t have access to education.

These reports show that the challenge is not only to ensure enrolment of children from these communities but also to ensure that they are retained and able to complete basic education, as they tend to repeat and drop out more than the students from the other communities. A periodic report titled “flash” report published by the Department of Education (DoE) in 2011-12 shows that only seven out of ten children enrolled in grade one reach grade five, as more than half of them leave school before reaching the lower secondary level.

According to the flash report, only one girl child from the Bankaria tribals is enrolled in lower secondary level. A data published two years before this report shows that as many as 22 children (14 girls and eight boys) had enrollment at the primary level.

The flash report also reveals that there are 13 disadvantaged IPs: Bankaria, Hayu, Kisan, Kusunda, Lepcha, Meche, Kushbadia, Raji, Raute, Singsa, Siyar, Surel, and Thudam who have less than 300 children enrolled at the lower secondary level while the number of their enrolment at the primarily level in the previous year was much higher. The situation of other IPs and minority groups is no different, either. This shows that a special attention is required to increase the access of the children from these communities to education.

A study conducted by Martin Chautari on participation in higher education in 26 constituent campuses under the Tribhuvan University shows that there are huge disparities among different socio-ethnic groups. The Hill Brahmins, Chhetris and Newars are, in general, overrepresented, considering their population as per the 2001 Census.

The Hill Brahmin/Chhetri and Newar communities respectively account for 68.4% and 12.3% of the total student population. Their proportional representation in the total population as reported in the 2001 Census is 30.89% and 5.48% respectively. Likewise, IPs groups (excluding Newars), Madhesis (excluding Tarai Dalits and Tarai IPs), Dalits (Hill and Tarai combined) and Muslims are underrepresented, going by their total population as reported by the 2001 Census. They constitute 12.7%, 4.0%, 1.4%, and 0.2% respectively of the total student population.

The flash report also reveals that there are 13 disadvantaged IPs: Bankaria, Hayu, Kisan, Kusunda, Lepcha, Meche, Kushbadia, Raji, Raute, Singsa, Siyar, Surel, and Thudam who have less than 300 children enrolled at the lower secondary level while the number of their enrolment at the primarily level in the previous year was much higher. The situation of other IPs and minority groups is no different, either. This shows that a special attention is required to increase the access of the children from these communities to education.

The same study shows the variations in student representation of these different social groups at the Bachelor’s and Masters levels. For instance, the participation of the IPs groups decreased by 13.8% of the total student population at the Bachelor’s level but only 10.3% of the total student body at the Masters.

On the other hand, the proportional representation of Hill Brahmins-Chhetris and Madhesis increased from 66.8% to 71.7%, and 3.6% to 4.7 percent respectively.

Genesis of IPs’ access to education

During the totalitarian Rana Regime, education was possible only for those who were close to the then ruling family and the Bahun priestly lines. The only medium was Sanskrit.

In 1995 AD (2011 BS), for the first time, the government formed Nepal National Education Council under the chairmanship of Rudraraj Panday, which recommended Nepali as the medium of instruction, ban of using other languages even in the informal sector and playgrounds. During the royal Panchayat Era, the ‘One language, one culture, one religion’ policy was adopted and other languages were completely suppressed. The result is that nearly a dozen indigenous languages have been extinct, according to linguists.

Particularly after the restoration of democracy in 1990, linguistic issues have been gradually gaining attention. Although some of the previous legacy relating to the suppression of the indigenous languages continues, the 1990 Constitution affirmed Nepal as a multilingual and multicultural nation state. The Constitution further stated that all languages spoken as mother tongues are the national languages, and further affirmed that every community residing within the country shall have the right to protect and develop its language, script, and culture, and equally the right to establish schools for providing education to children upto the primary level in their mother tongues.

Internationally, the government has expressed its commitment to ensure education of all children, including IPs, by signing conventions such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), World Conference on Education for All (EFA), the Dakar Framework of Action (2000), Millennium Development Goals (2000), UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) 2007, and ILO Convention No. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal peoples.

The Interim Constitution adopted in 2007 further guaranteed education upto the secondary level in mother tongues. The three-year Interim Plan (2007-2010) laid emphasis on the expansion and consolidation of early childhood education development program across the country, with priority for the excluded groups such as women, Dalits, IPs, Madeshis and people with disability, and through the provision of scholarships.

Internationally, the government has expressed its commitment to ensure education of all children, including IPs, by signing conventions such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), World Conference on Education for All (EFA), the Dakar Framework of Action (2000), Millennium Development Goals (2000), UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) 2007, and ILO Convention No. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal peoples.

Accordingly, the government has introduced two-tier policies as teaching mother tongues as optional subjects upto the higher secondary level and mother tongue as a medium of instruction, aiming to bring all children – especially from indigenous communities – to school. It has also launched an international initiative, the Education for All program and has been devising vulnerable community development framework since 2009. The government also scaled up multi-lingual education and community-level drive and so forth to ensure the participation of vulnerable groups, including IPs and other linguistic minorities, especially in the entire process of preparation of textbooks and other teaching materials.

Specifically targeting linguistic minorities and IPs, the Department of Education (DoE) Mother-tongue-based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) as a pilot program in 2004, primarily for eight mother tongues in seven schools in different districts – Tamang in Rasuwa, Aathpahria (Rai) in Dhankuta, Rana-Tharu language in Kanchanpur, Santhal and Rajbansi in Jhapa, Maithali and Urau in Sunsari, and Magar in Dhankuta. As the MLE yielded good results, in 2007, the government scaled it up to 21 schools. The school sector reform plan (2009-2015), another important education policy devised by the MoE, aims to implement mother-tongue-based multilingual education in 7,500 schools.

“Policy-wise, the government is very clear and sound for fully ensuring education for all, including IPs and linguistic minorities,” says Lawa Dev Awasthi, Director General of DoE.

According to Awasthi, besides having step-wise plan to scale up multilingual, bilingual education across Nepal, the Curriculum Development Centre (DDC), the sole government body entrusted to prepare school curricula, has developed textbooks in 24 mother tongues, and materials for the Non-Formal Education in 14 different languages. Ever since MTB-MLE was launched, numerous textbooks and teaching materials have been prepared upto the primary level with the involvement of the concerned communities.

“The sad thing is that, when it comes to the implementation part, the government is very weak,” says Yonjan-Tamang who also was the former National Technical Advisor in Multilingual Education Program, DoE/MoE.

“The implementation of multilingual, bilingual education at school will result not only in high attendance from the IPs and linguistic minorities but also high level of their cognitive capacity, self-pride and so forth,” says Prof. Dr. Yogendra Prasad Yadava, linguist and former head of Central Department of Linguistics, Tribhuvan University. “But there has been confusion whether to use mother tongue as a medium of instruction or just as an elective subject.”

Impressive, yet challenging

After the launching of MTB-MLE, the dropout rate of the students from the marginalized communities has gone down dramatically while the enrollment of students, especially female students, have increased, according to multilingual teachers.

“But we’ve been facing many difficulties due to inadequate teaching materials in mother tongues, and haven’t been able to get regular salary and adequate teaching trainings,” says Laxmi Rana Tharu, a multilingual teacher from Rastriya Primary School at Dekhtabhuli in Kanchanpur.

we’ve been facing many difficulties due to inadequate teaching materials in mother tongues, and haven’t been able to get regular salary and adequate teaching trainings.

Multilingual teacher from Shree Rastriya Yakata Primary School in Hallibari-9 of Jhapa, Bishnu Prasad Rajbansi, adds, “The students from Rajbansi and Santhal communities, who are instructed in their mother tongue, are now performing better in the final examinations than those who study in the Nepali language. However, we still face a critical shortage of resources and permanent teachers for multilingual education.”

Multilingual teachers from Rasuwa, Palpa, Sunsari, and Dhankuta also share similar views.

The way forward

Chancellor of Nepal Academy, Bairagi Kainla, says that as Nepal is a multilingual and multicultural country, we have to find ways for the best use of all the languages in all the sectors so that everyone, including the linguistic minorities and IPs, can feel proud. Similarly, IP activist Malla K. Sundar opines that as a language is a community’s heritage, it is the right of the concerned community to get education in their mother tongues.

All languages are the valuable jewels of a country. As in many other countries, all mother tongues must be promoted in all sectors, including education, administration, judiciary, and media. While MTB-MLE has helped in the promotion of mother tongues in the country, linguist Yonjon-Tamang says that native speakers also have a responsibility to be aware of their linguistic rights, right to education in their mother tongues, work for the preservation of their mother tongues. He adds that they should also keep on mounting pressure on the government to fully adhere to its commitments made at the national as well as international levels to promote these languages.

The number of enrolment of disadvantaged 13 IPs in lower secondary Level (from grade 6 to 8) Flash Report 2011-12, DoE

SN | IPs | Girl | Boy | Total |

1. | Bankariya | 1 | 0 | 1 |

2. | Hayu | 128 | 118 | 246 |

3. | Kisan | 63 | 55 | 118 |

4. | Kusunda | 11 | 4 | 15 |

5. | Lepcha | 104 | 88 | 192 |

6. | Meche | 138 | 125 | 263 |

7. | Kushbadiya | 8 | 12 | 20 |

8. | Raji | 27 | 28 | 55 |

9. | Raute | 9 | 9 | 18 |

10. | Singsa | 81 | 80 | 161 |

11. | Siyar | 20 | 14 | 34 |

12. | Surel | 4 | 9 | 13 |

13. | Thudam | 12 | 19 | 34 |

This table portrays that the number of enrolment of extremely disadvantaged 13 IPs have with less than 300 children in lower secondary education (from grade 6 to 8).

The number of enrolment of disadvantaged 13- IPs at primary level (from grade 1 to 5) Flash Report 2009-10, DoE

SN | IPs | Girl | Boy | Total |

1. | Bankariya | 14 | 8 | 22 |

2. | Hayu | 456 | 418 | 874 |

3. | Kisan | 757 | 850 | 1607 |

4. | Kusunda | 311 | 304 | 615 |

5. | Lepcha | 261 | 273 | 534 |

6. | Meche | 311 | 275 | 586 |

7. | Kushbadiya | 25 | 22 | 47 |

8. | Raji | 422 | 399 | 821 |

9. | Raute | 27 | 31 | 58 |

10. | Singsa | 122 | 103 | 225 |

11. | Siyar | 505 | 467 | 972 |

12. | Surel | 28 | 22 | 50 |

13. | Thudam | 128 | 163 | 291 |

Published in The Week edition of Republica English daily on : July 12, 2013

Link: http://www.theweek.myrepublica.com/details.php?news_id=57729

Also visit:

https://www.indigenousmediafoundation.org/

https://www.indigenoustelevision.com/live

https://www.indigenousvoice.com/en